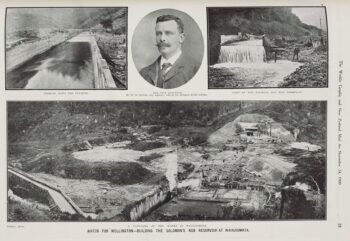

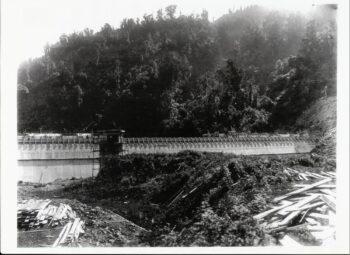

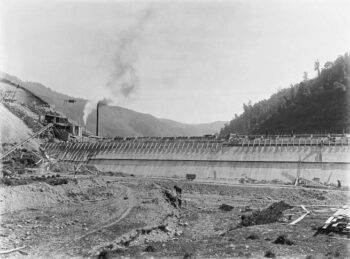

Built from 1908 to 1911, Morton Dam in the Wainuiomata River catchment was named after William Hobbard Morton, the Wellington City Engineer responsible for designing this reinforced concrete flat slab buttress dam.

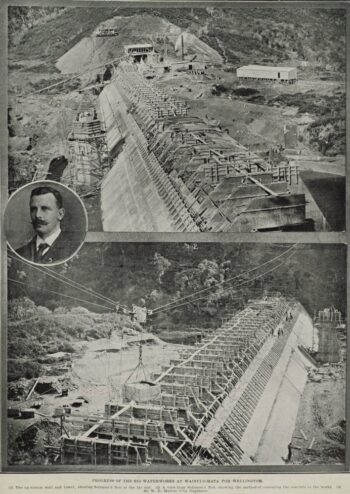

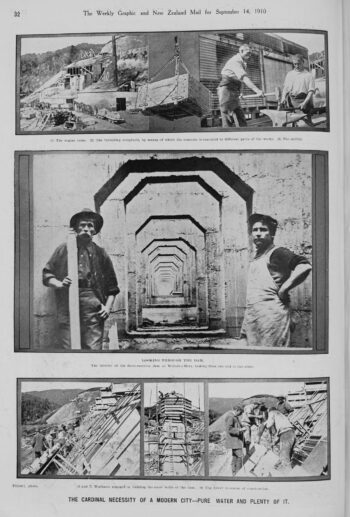

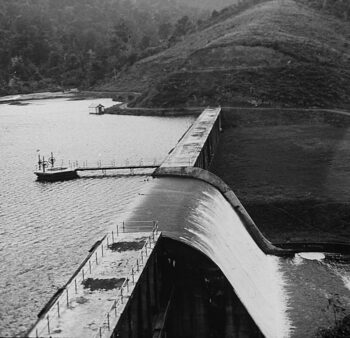

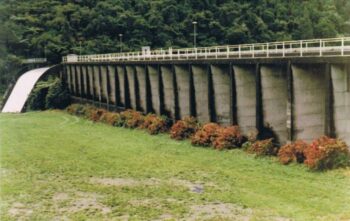

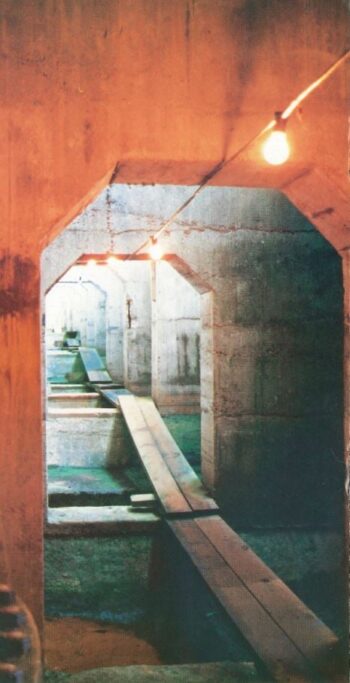

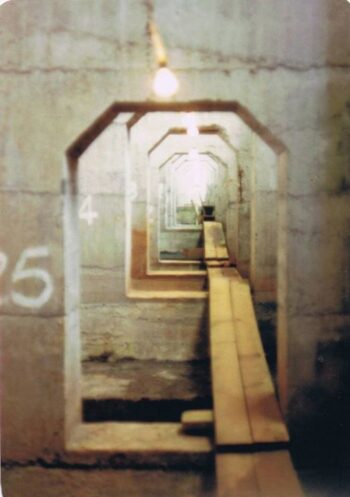

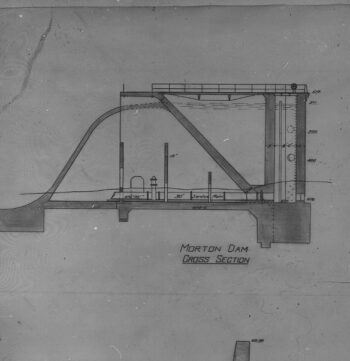

Morton Dam is one of New Zealand’s largest early concrete dams, with all its concrete work reinforced by steel rods. It spans 128 metres in length, stands 17 metres tall, and reaches depths of 8.5 to 9 metres with varying widths. Its foundation extends down to bedrock, with widths ranging from 1.7 to 2.4 metres. The dam features distinctive buttresses that form a series of open-fronted cells, with a spillway located at its northern end. Its upstream side is marked by a sloping wall, and a tower-house near the wall controls water flow. Built between 1908 and 1911, the dam was expanded in 1924 with additional weirs in the Wainuiomata Catchment and a pipeline from the Ōrongorongo Catchment. The dam cost around £50,000 to construct.

Decommissioning

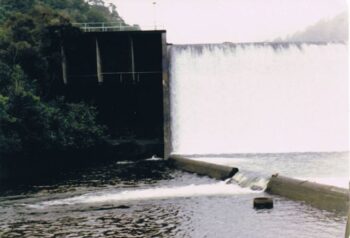

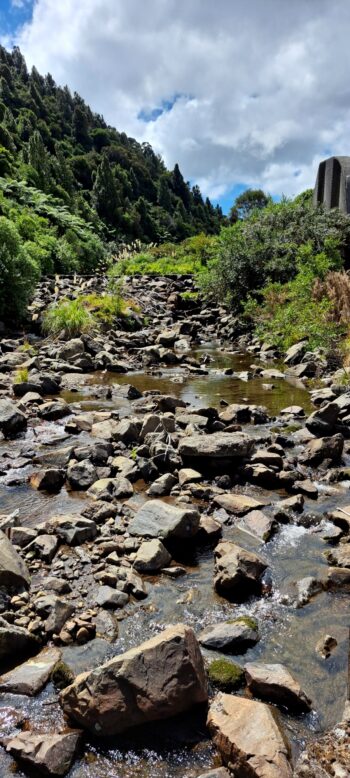

Despite being a sucessful solution to the Wellington region’s water needs, Morton Dam began to encounter major challenges, including vulnerability to earthquakes, silt build-up, and limited flood capacity. It was deemed as a structural liability and surplus to requirements with the development of alternative water sources by 1946. In 1987, the Greater Wellington Regional Council, which had managed the site since 1980, considered options for decommissioning the dam. To restore the river’s natural flow, reduce structural risks, and preserve the site’s engineering heritage, the Council removed part of the spillway in 1988, officially disconnecting the Morton Dam from Wellington’s water supply.

Despite being a sucessful solution to the Wellington region’s water needs, Morton Dam began to encounter major challenges, including vulnerability to earthquakes, silt build-up, and limited flood capacity. It was deemed as a structural liability and surplus to requirements with the development of alternative water sources by 1946. In 1987, the Greater Wellington Regional Council, which had managed the site since 1980, considered options for decommissioning the dam. To restore the river’s natural flow, reduce structural risks, and preserve the site’s engineering heritage, the Council removed part of the spillway in 1988, officially disconnecting the Morton Dam from Wellington’s water supply.

Subsequently, a new treatment plant was established, drawing water directly from weirs in both river catchments. This modern facility has a daily production capacity of up to 60 million liters, around the same supply as Morton Dam, around 15 percent of the water consumed in the Wellington urban area. Later in the 1990s, the associated Morton Dam Strainer Building was decommissioned.

Subsequently, a new treatment plant was established, drawing water directly from weirs in both river catchments. This modern facility has a daily production capacity of up to 60 million liters, around the same supply as Morton Dam, around 15 percent of the water consumed in the Wellington urban area. Later in the 1990s, the associated Morton Dam Strainer Building was decommissioned.

Today

Morton Dam still stands for historical purposes today. The engineer, William Hobbard Morton (1866–1923) played a crucial role as an engineer in the early 20th century with the significance of Morton Dam in engineering heritage being notable. It stands out as the initial and largest of just two reinforced concrete buttress dams constructed in New Zealand.

Morton Dam still stands for historical purposes today. The engineer, William Hobbard Morton (1866–1923) played a crucial role as an engineer in the early 20th century with the significance of Morton Dam in engineering heritage being notable. It stands out as the initial and largest of just two reinforced concrete buttress dams constructed in New Zealand.

Currently, the evaluation of the dam is underway for potential inclusion on the New Zealand Heritage List / Rārangi Kōrero, designated as No. 1836 (Category 2). Once confirmed, it will be added to the Hutt City Council’s Schedule of HNZPT Listed Items.

There is however a contradictory plan to revive Morton Dam to enhance future water supply to the Wellington region. Wellington Water has conducted a recent “comprehensive water supply strategy update” to examine long-term supply and demand options beyond the next decade. Among these options is the recommissioning of the Morton Dam to meet the needs of a growing population.

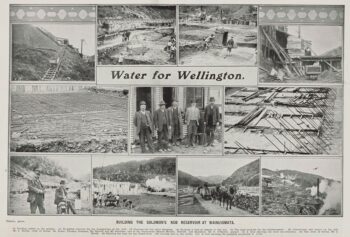

Construction site (1908 – 1911)

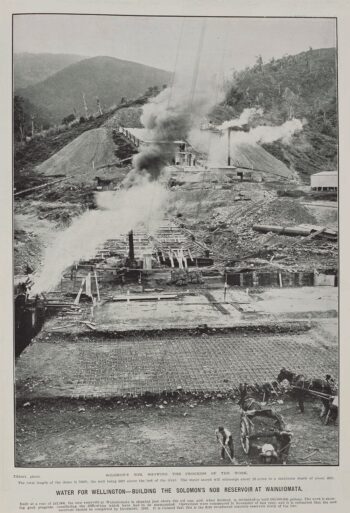

From the construction site, referred to as The Knob, 18-inch steel pipes extended beyond the old reservoir’s mouth. These pipes, ultimately intended to carry fresh water from the new dam to the city, were temporarily used to divert muddied water away from the worksite. Manufactured in New Zealand, the pipes were made by Nephau Fergusson in Auckland, with additional spiral pipes produced in Wanganui. This company, which had supplied pipes for major projects in the US, typically manufactured close to project sites.

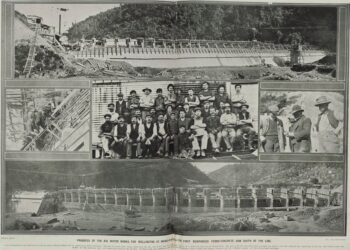

Sixty-five workers, including various tradesmen, were engaged in the contract. The machinery at Solomon’s Knob was housed in a large galvanised shed, with separate workshops for carpentry and blacksmithing. Although finding skilled navvies (manual labourers working on civil engineering projects) had occasionally been challenging, the contractors were eventually fully staffed, with the plant for the project valued between £3000 and £4000.

Sixty-five workers, including various tradesmen, were engaged in the contract. The machinery at Solomon’s Knob was housed in a large galvanised shed, with separate workshops for carpentry and blacksmithing. Although finding skilled navvies (manual labourers working on civil engineering projects) had occasionally been challenging, the contractors were eventually fully staffed, with the plant for the project valued between £3000 and £4000.

Additionally, an aerial “flying fox” wire, equipped with a two-ton gravel hopper, significantly expedited the work. This setup allowed tasks that once took a week to be completed in a single day, as the “flying fox” moved gravel at 300 feet per minute.

Additionally, an aerial “flying fox” wire, equipped with a two-ton gravel hopper, significantly expedited the work. This setup allowed tasks that once took a week to be completed in a single day, as the “flying fox” moved gravel at 300 feet per minute.

Navvy-town

During construction, a worker’s settlement known as “Navvy-town” emerged at the end of the tramline at Solomon’s Knob. Here, between 60 and 70 men, employed by the contracting firm of Martin, Hurrell, and Snaddon, worked on the dam. The camp included “tents” with wooden sides and ends, as well as several substantial huts scattered throughout.

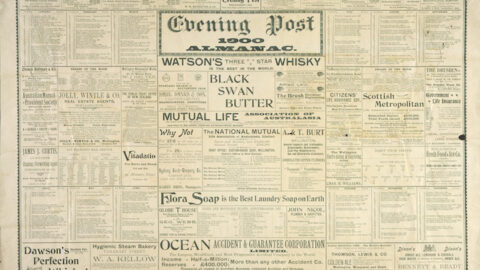

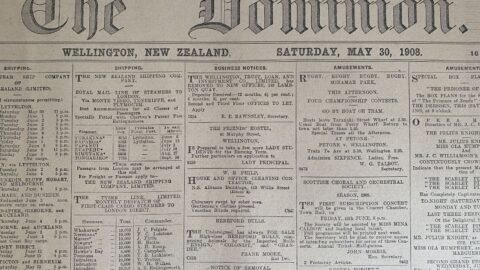

Tenders for construction

When the City Council called for tenders for the construction of the Solomon’s Knob Dam (later renamed Morton Dam), contractors were required to deposit £500 as a guarantee of good faith. J. O’Donnell and Co.’s tender was initially accepted as the lowest bid at £40,035, but the company later withdrew, declining to proceed. Subsequently, Messrs Martin, Hurrell, and Snadden’s tender was accepted at a revised price of £46,424. At a Council meeting, the Finance and Property Committee recommended denying O’Donnell’s request for a deposit refund, citing the contractor’s failure to complete the agreed contract.

The Mayor, Hon. T. W. Hislop, explained that, although O’Donnell may have withdrawn prior to formally receiving the acceptance notice, the Council’s acceptance was delivered before his withdrawal reached the Mayor. The committee confirmed that the Council was within its rights to retain the deposit to ensure consistency in contract adherence. Councillor Biss emphasised that showing leniency would set a risky precedent, leading others to expect similar consideration. Consequently, the report recommending the deposit forfeiture was adopted.