Wainuiomata’s Role in the Struggle to Supply Water to the Wellington Region.

The Wainuiomata/Orongorongo Water Catchment Area, spanning 7,600 hectares in the eastern Remutaka Ranges, has a rich history of infrastructure projects that have shaped Wellington’s water supply.

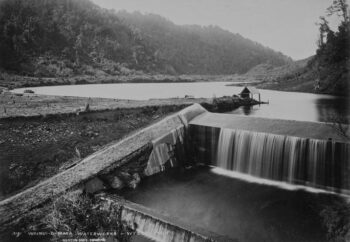

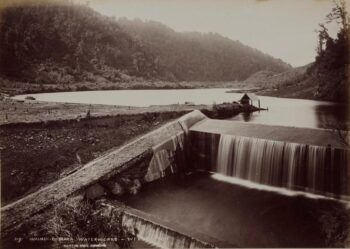

The Wainuiomata Waterworks project was a major undertaking led by Wellington City Council (WCC), involving nearly 100 contracts during construction. However, post-construction challenges arose, including storm damage to the newly built weir, causing leaks and requiring repairs. The pipeline also faced recurring faults, with one end of the pipe bridge over the Hutt River destroyed in a flood, leading to extensive repairs and supply disruptions.

Today, five low dams (weirs) with intakes and pipes supply water to the Wainuiomata Water Treatment Plant, providing 15% of Wellington’s annual water supply from the Wainuiomata River and George Creek. In the Orongorongo Valley, additional weirs on the Orongorongo River, Big Huia Creek, and Little Huia Creek contribute 5% more. A 3.2-kilometre access and pipeline tunnel connects the two catchments, ensuring a steady and reliable water supply for the region.

The Wainuiomata Supply Project (1878–1884)

By 1878, the city experienced severe water shortages, leading to public complaints, particularly about the lack of a night-time supply. In response, metering was introduced for extraordinary water use at a rate of one shilling per 1,000 gallons (4,500 litres), along with fines for wastage.

That same year, the railway station caught fire, but there was no water in the pipes to extinguish the blaze. It became clear that a new water source was urgently needed. City Engineer Mr J.N. Baird identified the Wainuiomata Valley, located 17 miles (27 km) from Wellington, as the most promising site for a new supply.

From 1878, purchase began for securing the catchment area, and a total of 8,400 acres was eventually purchased to ensure the purity of the supply. The scheme itself provided for the construction of a small earth dam in Sinclair Valley, north-east of the tiny settlement of Wainuiomata, on the Wainuiomata River Water was then diverted into a concrete water race over one mile (1.5 km) long, close to the junction of Wainuiomata Stream (then known as Moores Creek). From there, water was carried through six miles (9.5 km) of 30-inch (750 mm) cast iron pipeline, passing through two tunnels beneath the Waiwhetu Hills to Gracefield. From there, an additional eight miles (13 km) of 24-inch (600 mm) pipeline was laid around the head of Port Nicholson to the city. The project also required the construction of two pipe bridges over the Hutt River and Waiwhetu Stream (then known as the Waiwhetu River.

The Challenges of the Wainuiomata Water Supply (1881–1887)

The entire undertaking was fraught with difficulties. Travellers using the previously isolated and hazardous Hill Road endured delays caused by the slow-moving wagons transporting pipes to the site. In 1881, a tunnel collapse further hindered progress, while severe floods in October and November 1883 inflicted extensive damage on the partially constructed dam.

The project faced yet more setbacks as the completion date neared. Water was scheduled to be supplied to Wellington on Anniversary Day, 22 January 1884, and in preparation, the mains were filled on the 20th and 21st as far as Petone. However, a burst occurred within the long tunnel, followed by another failure on Petone Beach. Then, on Anniversary Day itself, a major flood washed away part of the dam.

Three years later, issues persisted. With the Wainuiomata mains shut off for headrace repairs, a devastating fire broke out in Panama Street, Wellington. Unable to be controlled due to the lack of water, the blaze intensified public frustration, leading to the establishment of a Waterworks Investigation Committee. Heated disputes erupted between Mr Baird and the new City Engineer, Mr B. Loughrey, regarding the design and construction of the headrace and the overall scheme. Despite the controversy, the committee ultimately concluded that there was “no grave defect in any part of the Wainuiomata Waterworks Scheme”.

Growth, Demand, and the Strain on Wellington’s Water Supply (1880s–1890s)

Despite its challenges, the Wainuiomata water supply brought security and change to the region. In Wainuiomata Settlement, the establishment of the waterworks transformed the community. The arrival of 70 workers had a noticeable impact, and the reservoir became a popular picnic and sightseeing destination for Wellingtonians. Additionally, the installation of a telephone link to Wellington, recommended by the Waterworks Investigation Committee, helped end the settlement’s isolation and stimulated its growth.

For Wellington, however, the security of a reliable water supply was short-lived. By 1887, the Wainuiomata system was expected to provide a maximum of 80 gallons (176 litres) per person per day for the city’s 26,000 residents and to accommodate double that population within a decade. Yet, just three years later, an exceptionally dry season once again led to water shortages in the city.

Wellington’s population expanded dramatically during the 1880s and 1890s, driven by a steady influx of immigrants arriving by ship. Between 1874 and 1894, the city’s population soared to 43,000, an astonishing 370% increase. As new suburbs developed beyond the city centre, securing a reliable water supply became increasingly critical for their future growth.

Petone, recognising the need for its own water infrastructure, applied to the Wellington City Council for access to the Wainuiomata water supply but was unsuccessful. This rejection, along with the pressing necessity to secure an independent water source, led to the formation of the Petone Borough Council in 1888. Other emerging suburbs, particularly those closer to the city centre, also sought access to Wellington’s water supply, highlighting the growing strain on existing resources.

The rapid expansion of Wellington and its surrounding suburbs ultimately underscored the need for major upgrades to the region’s water infrastructure, leading to further investments in reservoirs, pipelines, and municipal water management.

In Wainuiomata, tree planting initiatives were introduced, and the Wellington City Council granted permission to the Acclimatisation Society to allow deer breeding in the area. Meanwhile, improvements were made to the existing water supply infrastructure. New pipelines were laid from Willis Street to connect with the main supply at Karori Reservoir, ensuring continued service in case of a shutdown of the Wainuiomata system.

Despite these enhancements, the 1890s saw the introduction of new water restrictions. Initial confidence in the abundance of the Wainuiomata supply led to excessive use, including powering water engines, hydraulic lifts, and even street lighting. These practices were eventually prohibited to conserve water for domestic use. To curb wastage, metering was introduced for extraordinary consumption, a Water Inspector was appointed to address excessive use, and fines were imposed for water waste.

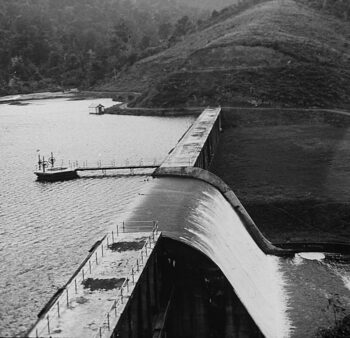

Lower Dam

The first catchment for Wellington’s water supply was in Karori, but it was clear that another site was needed as Wellington’s water needs exceeded supply. The Wainuiomata Valley, located adjacent to the Hutt Valley and Eastbourne was selected in 1878 as the new water catchment area to supplement the supply from Karori. Construction of a small concrete dam took place in Sinclair Valley and the same year, 27 kilometres of pipeline to Wellington were laid. Despite challenges like flooding and pipe bursts in the ensuing years, by 1887, the Wainuiomata Scheme provided 176 litres daily, enough for 26,000 people.

Challenges, Public Health, and Infrastructure Upgrades (1900–1904)

By 1900, it had become clear that Wellington required a supplementary water source. Both the Karori and Wainuiomata supplies had proven inadequate due to rising population growth, increasing demand, and a lack of accurate rainfall records. Additionally, suburbs outside Wellington were increasingly seeking access to the established supply. Recognising this urgency, the City Council in 1900 formally requested that the City Engineer provide recommendations on the best means of increasing the water supply.

In 1900, City Engineer Mr R.S. Rounthwaite submitted a report to the Wellington City Council, recommending significant improvements to the city’s water infrastructure. He proposed replacing the old covered race at Wainuiomata with a 30-inch (750 mm) cast iron pipeline. This upgrade, completed between 1902 and 1903, also included the installation of a new Venturi meter to allow for more accurate measurement of the water delivered to the city.

More importantly, Rounthwaite advocated for the construction of a new concrete dam at Wainuiomata and the installation of new mains to transport water to Wellington. However, despite these recommendations, water shortages persisted, exacerbating the city’s growing hygiene concerns. As Wellington’s population expanded rapidly, the City Council struggled with sanitation issues. Typhoid cases continued to emerge, and an outbreak of plague in Sydney, Australia, led to the establishment of a plague hospital on part of the Town Belt at Berhampore. To combat the risk of disease, laws were introduced requiring households to connect to the sewerage system, and residents were mandated to purchase iron refuse bins, which were regularly collected by Council carts. Additionally, rats delivered to the city’s incinerator, known as the “Destructor,” were bought for 2d or 3d each as part of efforts to control the spread of disease.

Fearing that water shortages could further compromise public health, the Council established a special Waterworks Commission in 1902. The Commission endorsed the City Engineer’s proposals for additional storage at Wainuiomata and the acquisition of the Karori Stream catchment area. However, these recommendations were ultimately rejected by the ratepayers.

In 1904, Mr W.H. Morton took over as City Engineer and again pushed for new storage reservoirs at Wainuiomata and Karori, the purchase of the Karori Stream catchment area, and the extension of the 30-inch (750 mm) pipeline to connect with a proposed new water reservoir. He also recommended expanding water services to the recently incorporated suburbs of Melrose, Brooklyn, Vogeltown, Island Bay, Lyall Bay, Kilbirnie, Hataitai, Roseneath, and Kelburn, as well as major extensions to the city’s reticulation system.

The year 1904 was particularly challenging, marked by earthquakes, droughts, and floods—all of which further tested the limits of the city’s two existing waterworks and reinforced the urgent need for additional water supplies. This time, the proposals for new water storage infrastructure were accepted, paving the way for future expansions, including the Upper Dam at Karori.

Overcoming Challenges to Meet Growing Demand (1907–1912)

The new Wainuiomata water project faced numerous challenges. It required the diversion and damming of the stream at Solomons Knob, along with the construction of new roads and bridges in rugged, poorly accessible terrain. The dam, built using reinforced concrete with a cellular section, measured 540 feet (164 metres) in length and 41 feet (12.5 metres) high from the streambed to the bywash below. The resulting reservoir had an impounding capacity of 107 million gallons (485 million litres).

Completed in 1911, the dam was named the Morton Dam, in recognition of City Engineer W.H. Morton’s contributions to its construction. Alongside the dam, Morton also recommended the duplication of the old 24-inch (600 mm) cast iron mains from Gracefield to the city. The original pipeline had long been prone to leaks and breakages, particularly after earth tremors, as its route along Hutt Road followed the Wellington Faultline.

One of the most severe failures occurred in 1907, when a major flood in the Hutt River destroyed 114 feet (35 metres) of the pipe bridge, causing a significant break in the Wainuiomata main. Repairs took 21 days, with work continuing around the clock.

In 1908, and again in 1910, Morton submitted reports recommending the construction of a duplicate 21-inch (530 mm) main, which would connect to a 2-million-gallon reservoir at Bell Road, Brooklyn, with an additional connection to the city’s reticulation network at Thorndon Quay to provide backup in case of pipeline failures. This duplicate main, completed in 1912, increased the Wainuiomata water supply by 237 million gallons (1,075 million litres) in its first year of operation.

However, despite these expansions, demand continued to outpace supply. Within a few years, it became evident that yet another water source would be required to meet the city’s growing needs.

Morton Dam

As Wellington’s population grew, more water was needed. In 1904, work began on the larger Morton Dam, completed in 1911 behind the lower dam, increasing daily output to 2.9 million litres. In 1912, a second pipeline was laid to Karori. Standing 17 metres high and 128 metres long, Morton Dam is one of New Zealand’s early concrete dams. Its design features open-fronted cells, a spillway at the western end, and an inclining upstream wall. Named after William Hobbard Morton (1866–1923), Wellington City Engineer, it was a pioneering reinforced concrete flat slab buttress dam.

As Wellington’s population grew, more water was needed. In 1904, work began on the larger Morton Dam, completed in 1911 behind the lower dam, increasing daily output to 2.9 million litres. In 1912, a second pipeline was laid to Karori. Standing 17 metres high and 128 metres long, Morton Dam is one of New Zealand’s early concrete dams. Its design features open-fronted cells, a spillway at the western end, and an inclining upstream wall. Named after William Hobbard Morton (1866–1923), Wellington City Engineer, it was a pioneering reinforced concrete flat slab buttress dam.

The Orongorongo Water Supply (1921–1926)

The idea of using the Orongorongo Valley as a water source for Wellington was not new. As early as 1887, a report to the Waterworks Investigation Committee on faults within the Wainuiomata waterworks suggested that the Orongorongo River should be utilised. However, this proposal was dismissed by City Engineer Mr B. Loughrey, who insisted that the existing water supply was “as clear as crystal” and that the Orongorongo should be left to future generations.

By 1910, City Engineer Mr W.H. Morton took a different stance. He proposed that the Government be approached with the aim of setting aside part of the Orongorongo catchment as a Waterworks Reserve. Over the following years, various schemes were considered for tapping into the Orongorongo supply.

In 1919, Morton put forward a major proposal that included:

- The construction of a large storage reservoir in the lower Wainuiomata Valley.

- A tunnel to tap into the Orongorongo Stream.

- Increased pipeline capacity to transport the additional water supply.

The Orongorongo water scheme was an ambitious project with an estimated cost of £540,650. Construction began in 1921 and was completed in 1926. The project involved building weirs on the Orongorongo River and its tributaries, as well as constructing a 3.2 km tunnel to connect the Orongorongo and Wainuiomata valleys.

Modifications to the Orongorongo Water Scheme

In 1920, the initial Orongorongo water scheme was modified due to the unexpected depth required for the dam foundations. In response, City Engineer W.H. Morton proposed an alternative plan: a tunnel would be drilled from the Wainuiomata Valley into the Orongorongo Valley, allowing water to be conveyed directly to the Lower Karori Reservoir.

The project included:

- Construction of a weir intake at 800 feet (260 metres) above sea level.

- A 21-inch (530 mm) steel pipeline, carrying water through the tunnel to the Wainuiomata Valley and onwards to the Lower Karori Reservoir, covering a total distance of 34 km.

This additional supply was expected to maintain a daily consumption rate of 74 gallons (335 litres) per person, supporting a population of 130,000 for 15 years (15/ii). The estimated cost of the project was £337,232, and a loan was raised in 1921 to commence construction.

Orongorongo Tunnel Construction

The Orongorongo Tunnel, completed in 1924, measured 7 feet (2 metres) high, 7 feet wide, and 2 miles (3.2 km) long. It was built using a co-operative labour system, under a contract between a tunnelling party led by Mr R. Semple (who later became Minister of Works in the 1935 Labour Government) and the Wellington City Corporation. The Corporation provided tools, materials, equipment, and on-site worker accommodation, which included the construction of a powerhouse powered by the Wainuiomata water supply.

Challenges in Constructing the Orongorongo Intake Weir

One of the biggest challenges in the Orongorongo project was access to the site. To transport lighter materials, a four-mile (6.5 km) pack track was cut through the bush, rising 300 metres between the Wainuiomata and Orongorongo Valleys.

For heavier materials, a complex transport system was required:

- Trucks carried materials 45 km to the mouth of the Orongorongo Stream.

- From there, horse teams transported materials 22 km upstream along the riverbed to the tunnel entrance.

- This journey involved crossing numerous fords and rough shingle beds, with side roads cut through the bush where the riverbed was too narrow for horses to pass.

Approximately 600 tons of steel water mains, cement, timber, and compression plant equipment were transported using this challenging route, overcoming significant logistical difficulties to complete the project.

Completion of the Orongorongo Water Scheme

The harsh geography of the Orongorongo site significantly influenced the design of the water scheme. Due to the remote and rugged terrain, the Lockbar process was used to locally manufacture lightweight steel pipes, making transportation and installation easier. Additionally, the presence of frequent shingle slips and deposits made the construction of a storage dam impractical. Instead, only a weir intake was built, though initial concerns arose regarding whether the intake gratings could be kept clear of shingle.

Despite these challenges, the Orongorongo project was completed in 1926, two years after City Engineer W.H. Morton’s death. The gravity-fed system carried water from the Orongorongo Valley to the Lower Karori Reservoir, supplying an additional 6 million gallons (27 million litres) per day to Wellington.

Three branch lines were connected to distribute the Orongorongo water supply to the Karori, Onslow, and Kelburn reservoirs. However, these feeder mains only operated when the terminal valve main at Karori was shut down.

The Orongorongo-to-Karori pipeline was installed using a pipe bridge over the Hutt River, ensuring secure passage over the waterway. Additionally, pipeline sections were strategically placed near the Karori Lower Dam, further integrating the new supply into Wellington’s existing water infrastructure.

Orongorongo Valley Water Catchment

Continued population growth, along with dry spells in 1915-17 and 1919, nearly exhausted the reservoirs, prompting the council to seek a new water source in the nearby Orongorongo Valley. In 1921, work began on three weirs, along with a 3.2km tunnel and pipeline connecting to the Wainuiomata Treatment Plant. The highest point in the Wainuiomata Catchment reaches 800 meters above sea level, marking the boundary between the Wainuiomata and Orongorongo catchments.

Continued population growth, along with dry spells in 1915-17 and 1919, nearly exhausted the reservoirs, prompting the council to seek a new water source in the nearby Orongorongo Valley. In 1921, work began on three weirs, along with a 3.2km tunnel and pipeline connecting to the Wainuiomata Treatment Plant. The highest point in the Wainuiomata Catchment reaches 800 meters above sea level, marking the boundary between the Wainuiomata and Orongorongo catchments.

A History of Abandoned Projects and Environmental Considerations (1970s)

In the Wainuiomata region, several dam projects were proposed but never realised, primarily due to geological and environmental concerns. In 1925, plans were made for a third dam approximately a mile downstream from the existing Wainuiomata Dam. This project would have inundated the valley below the caretaker’s residence, including the main access road. However, it was ultimately abandoned, likely due to concerns about the stability of the valley’s rock formations and potential earthquake risks.

In the 1970s, as water demand increased, geological surveys were conducted to assess the feasibility of constructing a new dam in Reservoir Valley. A 1978 environmental impact assessment evaluated the suitability of building an earth-rock dam intended to replace the Morton Dam. Despite these efforts, the project was not pursued, largely because of environmental concerns and questions about the stability of the valley’s geological structures.

These geological surveys left a lasting impact on the region’s landscape. Many of the tracks created for these surveys in the 1970s have been repurposed for recreational use. For instance, the Tana Umaga Track was originally established as a geological survey route to investigate rock structures for the proposed dam. Today, it offers visitors scenic views of the Lower Dam, which was transformed into a wetland in 2007, and the upper Wainuiomata River valley.

The Morton Dam, constructed between 1908 and 1911, was decommissioned in 1988 due to concerns about its seismic performance and reservoir siltation. Interestingly, as of May 2024, Wellington Water has been considering the possibility of reinstating the decommissioned Morton Dam to meet the region’s growing water demands. This proposal is still under investigation, with decisions expected to take a decade or more.

Proposed Dam

Old aerial photos of Reservoir Valley show a network of firebreaks created for geological surveys. One example is the Tana Umaga Track, established in the 1970s to assess rock formations for a proposed dam on the Wainuiomata River, though the plan was rejected perhaps due to concerns about rock stability, earthquake risk, and proximity to Homedale.

Old aerial photos of Reservoir Valley show a network of firebreaks created for geological surveys. One example is the Tana Umaga Track, established in the 1970s to assess rock formations for a proposed dam on the Wainuiomata River, though the plan was rejected perhaps due to concerns about rock stability, earthquake risk, and proximity to Homedale.

Decommissioned Dams and Replacement Weirs on the Wainuiomata River (1950s-1980s)

The Lower Dam, built in 1884, was decommissioned in the 1950s due to limited capacity and safety concerns. In 1969 or 1970, its spillway was lowered, converting the reservoir into a wetland, which is now a habitat for native birds.

The Morton Dam, completed in 1911, was decommissioned in 1988 due to seismic risks, spillway capacity issues, and reservoir siltation. A section of the dam was removed, allowing the Wainuiomata River to return to its natural course.

As of 2024, Wellington Water is considering reinstating the Morton Dam to help meet growing water demands, though this decision is still under review.

In the 1980s, two weirs were built on the Wainuiomata River and George Creek to replace the decommissioned Morton Dam. These weirs, along with the existing Ōrongorongo weirs, direct water to a treatment facility that supplies around 15% of Wellington’s water. This system ensures a steady water supply while avoiding the risks associated with large dams.

Weirs and dam decommissioning.

In the 1950s, the Lower Dam stopped supplying water, leaving the Morton Dam and Orongorongo weir to meet Wellington’s needs. Around 1969–1970, the Lower Dam’s spillway was lowered by a metre for safety, and sluices were opened. In 1989, safety concerns led to the Morton Dam’s decommissioning, with the reservoir drained and the dam breached to restore natural flow. It was replaced by two new weirs on the Wainuiomata River, alongside three existing weirs in the Orongorongo Valley. Today, the Wainuiomata River still flows over the Lower Dam’s spillway.

History of Water Treatment in Wainuiomata (1963-2005)

Following the Boxing Day flood in 1962, intense rainfall in the Wainuiomata and Orongorongo valleys inflicted damage on intake weirs, resulting in the transport of mud and silt into the city before the valve could be closed. Consequently, in 1963, the construction of a chlorination plant commenced to address both water supplies. Permanent chlorination and fluoridation facilities were then completed by 1964-65. Strainers were subsequently installed on the O-K main in 1967 and the Wainuiomata pipe in 1968.

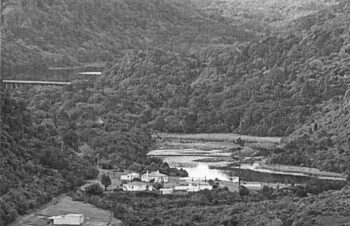

In 1993, a significant development took place with the construction of the Wainuiomata Treatment Plant. The plant supplies around 20% of Wellington’s water from the Wainuiomata and Ōrongorongo Rivers, plus George Creek, Big Huia Creek, and Little Huia Creek. It has a capacity of 60 million litres per day (ML/d) but typically produces 30 ML/d. The treatment process includes pH adjustment, coagulation, and dissolved air flotation to remove impurities. The plant primarily serves Wainuiomata, central Wellington, and its southern and eastern suburbs.

In 2005, improvements to the coagulation process enhanced water quality and reduced chemical costs by 20%. The plant remains essential to Wellington’s drinking water supply.

Chlorine Plant

The Wainuiomata-Orongorongo catchment area began chlorinating its water supply in 1963. In 1964, a permanent facility for chlorination and fluoridation was established. Strainers were added to the O-K main in 1967 and the Wainuiomata pipe in 1968.

Water Treatment Plant

The Wainuiomata Water Treatment Plant supplies treated drinking water to Wellington, Lower Hutt, and surrounding areas. Managed by Wellington Water, it uses coagulation, filtration, UV disinfection, and chlorination to meet strict water standards while ensuring efficiency and environmental protection.

The Wainuiomata Water Treatment Plant supplies treated drinking water to Wellington, Lower Hutt, and surrounding areas. Managed by Wellington Water, it uses coagulation, filtration, UV disinfection, and chlorination to meet strict water standards while ensuring efficiency and environmental protection.

Supplying Hydroelectric Power at the Wainuiomata Water Treatment Plant (2008-Present)

In 2008, an investigation into harnessing hydroelectric power at the Wainuiomata Water Treatment Plant was conducted. The proposal aimed to utilize the 100-metre head difference in the 5.6 km pipeline transporting water from the Orongorongo catchment to the treatment plant. By bypassing existing pressure-reducing valves, the available pressure head could drive a turbine to generate electricity. At a flow rate of 40 million litres per day (MLD).

Commissioned in May 2011, the generator utilizes the pressure from the 5.6 km pipeline transporting water from the Orongorongo catchment to the treatment plant. This system generates approximately 318 kW of electricity, meeting around 95% of the plant’s energy requirements. Any surplus electricity is fed into the local power grid.

Mini Hydro Power Generation

A hydroelectric generator was built to power a turbine and generate electricity for the Wainuiomata Treatment Plant. Water from the Orongorongo system is piped through a 5.6 km pipeline and tunnel, passing through a powerhouse before reaching the plant.

Water Conveyance in the Wainuiomata/Ōrongorongo Catchments (1880s-Present)

Water from the Wainuiomata and Ōrongorongo catchment areas is collected via weirs and intakes, then transported through a network of pipes and tunnels to the Wainuiomata Water Treatment Plant, before being distributed to Wellington. Initially, water was conveyed through the Waiwhetu Tunnel, a brick-lined tunnel built in the 1880s, which housed a 750 mm pipeline. In the 1980s, this was replaced by the Wainuiomata Tunnel, which incorporated part of an unfinished road tunnel from the 1930s to accommodate a larger 1,100 mm pipeline.

Most of the pipeline is buried or routed through tunnels, but some sections remain exposed, particularly at river crossings, where the pipeline either spans the waterway or is attached to bridges. These strategic placements ensure a reliable and efficient water supply while adapting to the area’s terrain.

Water Pipeline

River water is directed to a treatment facility via intake pipes and distributed through pipelines. In the Orongorongo Valley, three weirs transport water to the treatment plant via a tunnel, while weirs along the Wainuiomata River are piped to the same destination. From there, water is distributed to Wainuiomata, the Wellington City Business District, and the southern and eastern suburbs through a pipeline that eventually interconnects at Nguaranga with the Kaitoke to Karori pipeline, ensuring water security by enabling transfer between pipelines from multiple sources.

River water is directed to a treatment facility via intake pipes and distributed through pipelines. In the Orongorongo Valley, three weirs transport water to the treatment plant via a tunnel, while weirs along the Wainuiomata River are piped to the same destination. From there, water is distributed to Wainuiomata, the Wellington City Business District, and the southern and eastern suburbs through a pipeline that eventually interconnects at Nguaranga with the Kaitoke to Karori pipeline, ensuring water security by enabling transfer between pipelines from multiple sources.

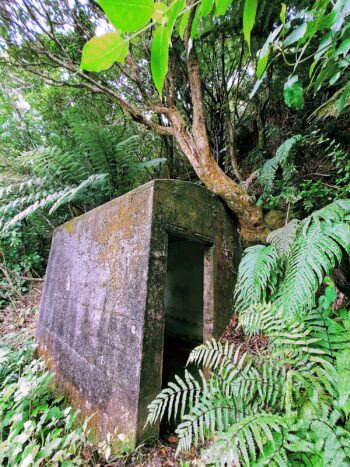

Tunnels

Tunnels in Wainuiomata were essential for supplying water to Wellington, providing a dependable route for water pipes through the hills both within and beyond the suburb. They also facilitated water transportation to the Orongorongo catchment and managed overflow and drainage from the old dam, ensuring system stability.

Tunnels in Wainuiomata were essential for supplying water to Wellington, providing a dependable route for water pipes through the hills both within and beyond the suburb. They also facilitated water transportation to the Orongorongo catchment and managed overflow and drainage from the old dam, ensuring system stability.

Partial Conversion of Wainuiomata Waterworks into a Regional Park (1980s–Present)

In the 1980s, the original dam infrastructure in Wainuiomata was decommissioned due to concerns about seismic resilience and sedimentation. The area up to this dam was subsequently opened to the public and designated as the Wainuiomata Recreation Area. In January 2022, it was officially renamed Wainuiomata Regional Park. In 2007, the decommissioned Lower Dam was transformed into a wetland, enhancing local biodiversity and providing new recreational opportunities. The park offers a variety of walking tracks, natural swimming spots along the Wainuiomata River, and serves as a gateway to the extensive lowland forests of the lower North Island. Additionally, the park houses the Wainuiomata Water Museum, located near the site of the old dam. The museum features a collection of historical artifacts and visuals related to the area’s water collection history, offering visitors insights into the region’s past.

Wetland Development

With the decommissioning of both dams, some decades later in 2007, a shallow lake and wetlands area was created. Today, it is home to native birds like bellbirds, kereru, and paradise ducks. In 2013, the lower dam and wetlands was opened to the public for the first time in over 129 years. To get there, you can walk along Reservoir Road to the end. This road is actually part of Gums Loop Walk, so you can also access it via the bush walk as it is a loop walk.

Wainuiomata Regional Park

With public access and tracks to the lower dam and surrounds, the area became known as the Wainuiomata Recreation Area. In 2022, it changed its name to Wainuiomata Regional Park. The park has numerous bush walks, swimming holes, and leftover artifacts from forgotten infrastructure belonging to the waterworks.