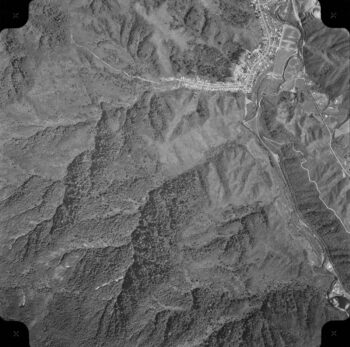

I charted the probable crash site of the Kittyhawk and aimed to investigate any additional potential locations.

I’ve been to the Kittyhawk site twice within the past fortnight, and revisited the area of the potential crash to gain a clearer understanding of the terrain. My objective today was to identify potential crash sites despite already locating a site that ticks all the boxes. I also aimed to exclude areas where the aircraft couldn’t have gone down given the known evidence.

I’ve been to the Kittyhawk site twice within the past fortnight, and revisited the area of the potential crash to gain a clearer understanding of the terrain. My objective today was to identify potential crash sites despite already locating a site that ticks all the boxes. I also aimed to exclude areas where the aircraft couldn’t have gone down given the known evidence.

In my previous adventures, I came across a site where six parts of a plane were scattered, indicating the likely location for the crash site. Situated significantly higher than the fuselage site in Skerretts Creek, the location stands as the highest site containing plane wreckage. This is pivotal, as it potentially marks the crash site and this location agrees with a 1969 aerial photograph that seems to depict what looks like an airplane in that exact location. Alternatively, if not the precise crash location, then the plane or parts may have come down from above via slips and precipitation, but I conclude that this is unlikely for a number of reasons.

In my previous adventures, I came across a site where six parts of a plane were scattered, indicating the likely location for the crash site. Situated significantly higher than the fuselage site in Skerretts Creek, the location stands as the highest site containing plane wreckage. This is pivotal, as it potentially marks the crash site and this location agrees with a 1969 aerial photograph that seems to depict what looks like an airplane in that exact location. Alternatively, if not the precise crash location, then the plane or parts may have come down from above via slips and precipitation, but I conclude that this is unlikely for a number of reasons.

Today’s agenda involved scrutinizing the area above the site to determine the likelihood of the crash occurring in that vicinity and to assess the probability thereof regarding other sites. Encouragingly, the terrain’s narrow slope suggested that the parts landed at the site because it is either the crash site or the craft or parts descended through a very strict and confined path above to the site’s location. Outside of that confined path, the plane or parts would likely have veered off into one of the creek arms to the side at some point, because the site is located on the ridge of a rounded spur.

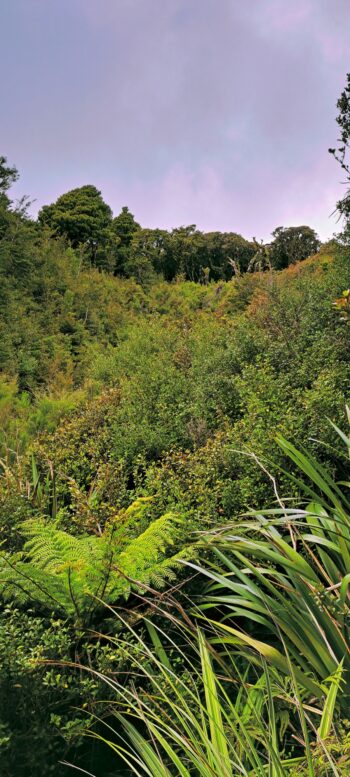

I started the mission by walking up the Whakanui Track from the top of Sunny Grove. You can also start this walk from Hine Road Reserve as the old entrance is still there. Once atop the ridge with a few photo stops onroute, I then connected to the McKerrow Track, which runs along the ridgeline to a peak of 706m. A distance before the peak, the ridge spans across the valley that contains Skerretts Creek, so I dropped down and started bush bashing through ferns and smaller trees. While I had been to the site twice before, I had trouble locating it the third time, testament to how easy it is to get lost in this place. It turned out that I did not go down far enough on my first attempt. But this also gave me a better lay of the land above the site, which was my intention anyway.

I started the mission by walking up the Whakanui Track from the top of Sunny Grove. You can also start this walk from Hine Road Reserve as the old entrance is still there. Once atop the ridge with a few photo stops onroute, I then connected to the McKerrow Track, which runs along the ridgeline to a peak of 706m. A distance before the peak, the ridge spans across the valley that contains Skerretts Creek, so I dropped down and started bush bashing through ferns and smaller trees. While I had been to the site twice before, I had trouble locating it the third time, testament to how easy it is to get lost in this place. It turned out that I did not go down far enough on my first attempt. But this also gave me a better lay of the land above the site, which was my intention anyway.

Once I descended down further, I found the the site after noticing some familiar trees and landmarks. I meticulously scanned the surroundings for additional plane debris, but came up empty-handed this time. I then proceeded to ascend the area above the site, tracing along the narrow corridor that might have been the trajectory of the crash had it occurred higher up. Much of this pathway proved too steep being a rock face, effectively ruling out this immediate steep section as potential crash site. While it could have been points of impact, any wreckage would likely have descended immediately from there. Once I was up and over the rock face, and further up the narrow corridor, I encountered another site resembling the original one. It featured a small flattish area with a sizable rock face above which was adorned with low vegetation over the rock. This alternate site, which I had actually mistaken for the original site during my search about one hour earlier while looking for the site, now emerged in my mind as another plausible candidate for the crash site, but there were no signs or debri from an aircraft located here.

Above this new potential site, I navigated another very steep rock face, which was even more challenging than the previous rock face, due to the thick bush type plants growing on the surface coupled with the steep gradient. There was obviously not much soil on the surface for taller plants to grow. But I couldn’t tell as the thick foliage obscured the ground entirely, leaving me to take each step blindly and unaware of where my feet were really landing. At one point my feet started slipping down the surface of the rock with the low vegetation holding me and stopping me from sliding down. Below me I could see the canopy of a small tree, so I knew that the gradient was steep despite not being able to truly see what was under this thick low growth. Basically I had to climb up this rock to get over it and it proved too difficult. So I went around the rock near a creek arm at two different locations before I was able to actually scale it near its top. I even lost my footing at one point and fell over. Fortunately, I managed to stay put and avoid sliding down the rock thanks to the thick vegetation.

Above this new potential site, I navigated another very steep rock face, which was even more challenging than the previous rock face, due to the thick bush type plants growing on the surface coupled with the steep gradient. There was obviously not much soil on the surface for taller plants to grow. But I couldn’t tell as the thick foliage obscured the ground entirely, leaving me to take each step blindly and unaware of where my feet were really landing. At one point my feet started slipping down the surface of the rock with the low vegetation holding me and stopping me from sliding down. Below me I could see the canopy of a small tree, so I knew that the gradient was steep despite not being able to truly see what was under this thick low growth. Basically I had to climb up this rock to get over it and it proved too difficult. So I went around the rock near a creek arm at two different locations before I was able to actually scale it near its top. I even lost my footing at one point and fell over. Fortunately, I managed to stay put and avoid sliding down the rock thanks to the thick vegetation.

Above this new rock face, I found myself on a less steep slope with sparse vegetation and scattered large trees. Although this area could also be considered a potential crash site, its lateral sloping to the sides increased the likelihood of any wreckage missing the highest known site with plane parts below, and instead, falling into the creek arms on either side as the area sloping toward these arms is larger than the area atop these slopes leading down the site.

Above this new rock face, I found myself on a less steep slope with sparse vegetation and scattered large trees. Although this area could also be considered a potential crash site, its lateral sloping to the sides increased the likelihood of any wreckage missing the highest known site with plane parts below, and instead, falling into the creek arms on either side as the area sloping toward these arms is larger than the area atop these slopes leading down the site.

As I ascended further, I wondered if the plane could have landed here, because it means it nearly made it over the ridge, which doesn’t agree with reports from people who visited the original crash site many years ago. Moreover, the greater the elevation of the crash site, the lower the probability of any remnants reaching the highest documented location with debris or fragments, as the likelihood of parts descending the slopes of the spur is substantially heightened. However, I do not dismiss the potential entirely. It’s plausible that the six parts I discovered were fortuitously washed down to the site, while the remainder of the aircraft may have descended into a creek arm, continuing its gradual descent over time.

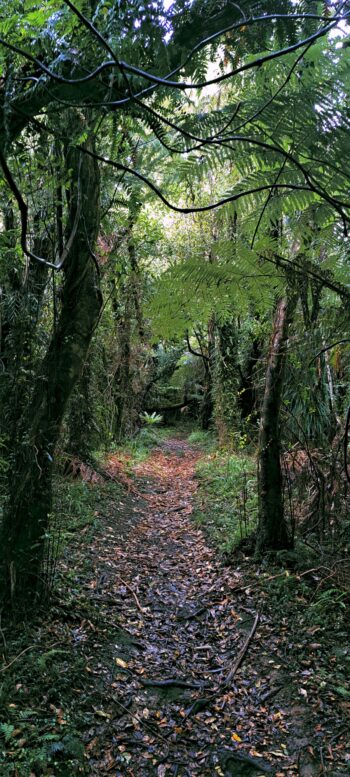

Soon after, I found myself amidst a more typical bush environment, characterized by ground ferns and densely packed trees. Soon, I rejoined the McKerrow track. At this point, I had a decision to make. With daylight still bright but getting a bit late, I pondered whether to retrace my steps along the McKerrow track and then descend via the Whakanui which I had done twice before in the last 2 weeks. Or should I explore an alternative route out, indicated on a Topo50 map I had seen the day before. Although the alternate tracks lacked designated names, I presumed there would be some signage to guide the way. How difficult could it be? Consequently, I chose to follow this route. However, this decision proved to be a misstep, albeit one from which I eventually emerged.

Upon later investigation, I believe that this unnamed track that came off the McKerrow is the old McKerrow Track. I think the McKerrow was rerouted in part. Regardless, this track was poorly maintained, although there were red tags affixed to trees to guide trampers along the route and there were numerous bait traps indicating that it might exist primarily for that reason. As I descended a ridge, I found it increasingly challenging to follow the track, particularly as the terrain opened up, making it difficult to discern the trail amidst more open terrain. Further, in the areas where the track was easier to spot due to thicker surrounding vegetation, this also meant these sections were darker due to a thick forest canopy coupled with dwindling evening light. Anyway, according to the map I saw, if I followed this track it would come to a juncture where I had the option to descend down to the Boys Brigade Camp located at Coast Road, or take a small connecting trail to Mt Crowther Track. I wanted to take the latter option because Mt Crowther Track would take me to the top of Sunny Grove and I was somewhat familiar with Mt Crowther Track, despite never walking its entire length.

Upon later investigation, I believe that this unnamed track that came off the McKerrow is the old McKerrow Track. I think the McKerrow was rerouted in part. Regardless, this track was poorly maintained, although there were red tags affixed to trees to guide trampers along the route and there were numerous bait traps indicating that it might exist primarily for that reason. As I descended a ridge, I found it increasingly challenging to follow the track, particularly as the terrain opened up, making it difficult to discern the trail amidst more open terrain. Further, in the areas where the track was easier to spot due to thicker surrounding vegetation, this also meant these sections were darker due to a thick forest canopy coupled with dwindling evening light. Anyway, according to the map I saw, if I followed this track it would come to a juncture where I had the option to descend down to the Boys Brigade Camp located at Coast Road, or take a small connecting trail to Mt Crowther Track. I wanted to take the latter option because Mt Crowther Track would take me to the top of Sunny Grove and I was somewhat familiar with Mt Crowther Track, despite never walking its entire length.

The challenge arose when I realized that this old McKerrow Track was longer than I had anticipated, necessitating swift movement to make the most of the remaining daylight. Eventually, I encountered a signpost, which initially seemed promising. However, it only indicated “Bivy Track” without any further explanation, leaving me uncertain about its destination. After scanning the surroundings for alternative paths and finding none, I reluctantly opted for the Bivy Track. Yet, hesitantly, I retraced my steps back to the signpost, recalling from the map that there should have been another track leading to the Mt Crowther Track at that spot. Regretting the time lost, I scanned for another track and found it.

The challenge arose when I realized that this old McKerrow Track was longer than I had anticipated, necessitating swift movement to make the most of the remaining daylight. Eventually, I encountered a signpost, which initially seemed promising. However, it only indicated “Bivy Track” without any further explanation, leaving me uncertain about its destination. After scanning the surroundings for alternative paths and finding none, I reluctantly opted for the Bivy Track. Yet, hesitantly, I retraced my steps back to the signpost, recalling from the map that there should have been another track leading to the Mt Crowther Track at that spot. Regretting the time lost, I scanned for another track and found it.

Being thankful for returning to the sign and finding the track, my next concern was whether this was the link track I thought it was, or was it a different route leading me away and potentially back uphill? With each passing moment, the fading light made it increasingly challenging to spot the track markers too. Contemplating the possibility of spending the night in this unfamiliar terrain if the track wasn’t going where I hoped it would, I was mindful of the sporadic rainfall, but I found some solace in the fact that I had packed a jacket, beanie, and a drink in my backpack.

Just as my worries peaked, a breakthrough emerged before me: an opening onto a firebreak. It was the Mt Crowther Track, noticeably wider with ample light due to a lack of canopy directly above. Relief washed over me. Now, all that remained was to descend to Sunny Grove, and my problems would be behind me. However, it’s crucial to always maintain respect for the bush no matter whether you are on a track or not. As I momentarily relaxed, I learned the hard way when I slipped down the steep gradient on the wet clay beneath my feet—not once, but twice. Refocusing on my descent, I made use of small manuka trees on the fringe of the track during the really steep sections to anchor myself. Eventually, I emerged from the wilderness unscathed, a humbling reminder of the importance of vigilance in the New Zealand bush.

Upon returning home and reviewing a map to trace this alternate route I took, I observed that the juncture of the link track and Mt Crowther Track was near the peak of Mt Crowther, which stands at 377 meters. According to a map, to walk up this peak takes 30 minutes from the bottom, near Sunny Grove. This meant the junction where the track came out on the track was perhaps around 300 metres, but probably more, as I was not quite at the peak. With 30 minutes to go up, I also think it takes that long to descend when it is slippery as you will likely slip and fall if you go faster. This means that it equates to roughly a 100-meter descent every 10 minutes, or 10 meters every minute, translating to 1 meter every 6 seconds. In short, this was one hell of a gradient. But a great track to run up if you were a fitness freak. I actually did see a guy run up this track one time, when I was investigating the two old water tanks, near the bottom of the Mt Crowther Track. Anyway, I was glad to be back on solid ground once I descended the slippery clay slopes of Mt Crowther Track after rain.

Indeed, it was a rewarding adventure, one that provided a greater workout than any previous bush exploration. I found satisfaction in pushing my limits. However, the journey also imparted a valuable lesson for me: when daylight wanes, prioritize familiar tracks for the return journey. Reserve unfamiliar paths for times when ample daylight allows for the correction of any missteps. And above all, maintain unwavering focus. Even on seemingly easier terrain, complacency can breed mistakes. Respect for the bush should remain constant, whether navigating through dense wilderness or along established trails. This experience served as a poignant reminder of the importance of vigilance and reverence for the New Zealand wilderness.

Regarding the objective of this mission, have I located the Kittyhawk crash site? The answer is that I’ve narrowed it down to three potential sites based on evidence and a thorough understanding of the landscape and gravitational forces. One of these sites is the probable location, supported by the presence of parts and alignment with an aerial photograph from 1969. The remaining two sites are plausible, situated above the likely location and offering a flattish surface for a plane to settle. However, these alternative sites lack any evidence of plane wreckage.