The Tourist.

NARRATIVE OF A WALKING TOUR TO LAKE WAIRARAPA BY THE SEA COAST

The sun was not just gilding the hill-tops with his morning beams—not by two good hours—as my companion Heliodorus and myself left the slumbering city behind us, and started off on what we intended to be a walking tour round the coast to the Wairarapa Lake, returning by way of Featherston and the Rimutaka Hill.

We commenced operations by scaling Mount Victoria, and reached Evans Bay just at the further side of the Patent Slip. Here we found two early fishermen hauling in their net, with a horse and cart in attendance, thus removing from my mind an unjust impression it once retained that “All alive, oh!” was “All a lie, oh!” One has to get up early to search for truth, and no doubt these finny victims were as much alive and awake as many of their destined consumers by the time they reached Wellington.

We then made straight across the peninsula for the pilot-station, where we roused from his slumbers the good Palinurus who had kindly promised to have us put across.

Arrived at the other side of the Heads, the real hard work of the day commenced. We climbed the hill by the lighthouse, and so cut off a good deal of Pencarrow Head, and went our way on through gorse and manuka, down devious sheepwalks, till we came to a lagoon, sacred no doubt to the divinities who preside over the interests of ducks and eels.

Here we found a punt, and some spirit of mischief—probably the same which has ever tempted the youth of all ages per vetitum nefas—put it into the head of Heliodorus that we should devote this somewhat fragile skiff to our own purposes. With difficulty forcing a way through tall rushes, we at last emerged on the shilling bosom of the lake, which, in accordance with the plagiaristic nomenclature in fashion in the colonies, we named Nyanza.

After pulling about for a little, we landed on the other side, and climbing a hill, there was one of the most glorious panoramas spread out before us that it was ever my fortune to witness. The ocean lay below, as blue as indigo, and as smooth as a steel mirror; the Kaikouras rose before us, with that softened outline which only distance and the pure morning air can lend. Facing to the right, the picture was filled in by the sloping headland of Pencarrow, and the wooden prison walls of the Wainuiomata.

However, as our intention was to reach the Perry Inn at the mouth of the lake that evening, we could not stay very long admiring the view. So after giving the time of day to a solitary European who was boiling down a small bottle-nose whale, or a fish very like one, which had been stranded on the beach, we again made a short cut inland and crossed the Wainuiomata about a mile from its mouth.

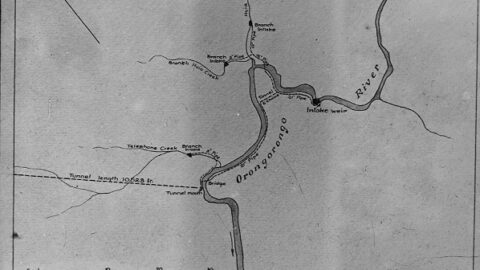

From here to Orongorongo is about three miles, over a very fatiguing shingly beach; and it was noon when we came in sight of that prettiest of homesteads. We hallooed to a small boy who was herding kine to inform us whether this was Orongorongo or not, but, doubtless terrified by the ruffian-like aspect of Heliodorus, he made away as hard as he could run.

However, we held on, and ran him to earth in a kitchen, where we had half an hour’s rest, and refreshed the inner man. Here we were shown some specimens of gold, purporting to be obtained from the neighbouring hills; to my vision, however, they seemed more like pyrites. There certainly was a great deal of pyrites discernible in all the pieces of rock.

Here we expected to meet with Nepos, but instead he overtook us on horseback, with two companions, after we had got about a mile further on, and as we were sampling the water of one of the thousand and one fluvial responsibilities which Palliser Bay takes charge of. Not even the charm of our company, however, could persuade them to come on with us for the rest of our journey.

The full expanse of Palliser Bay now lay open to our view, and we saw in the far distance the sun-glare flashing on the windows of the hotel which was destined to shelter us that night. Distance here did not lend much enchantment to the view, for we knew we had sixteen miles of stiff beach to walk over before we could reach it.

Where we could keep close up under the cliffs the walking was generally good, but sometimes for miles it was necessary to trudge along in the villainous shingle. Here one of us—Heliodorus, I think—remarked that the poet could never have had New Zealand in his head when he sung “And man alone is vile.”

However, the beautiful glimpses of bush and mountain scenery which every opening gully revealed went far to reconcile us to our troubles and inconveniences. Here and there we came upon a grove of karaka trees, fully justifying the popular definition of the word “lucus,” so cool and dark that one might imagine the spirit of Egeria to haunt it, where grateful cattle took refuge from the noontide heat.

But by far the most frequent specimens of fauna we met with were goats—goats of all patterns, hues, and ages, and in all sorts of dizzy inaccessible places—and paradise ducks. Their tameness was shocking to see till you got within a stone’s throw of them, when you were disagreeably reminded of the advantage pinions have over legs.

When we rounded the foot of the bay we left the beauty of the scenery behind us, and both cliffs and beach became very uninteresting, the former being bare of vegetation, and composed of sand and clay, interspersed with boulders and gravel. They gradually decreased in height till they reached the edge of the lake, where they turned up-country and formed its western boundary.

The beach consisted of inexorable shingle and loose sand, unyielding only in its yielding nature. So loose and permeable is the whole beach along this coast, that none of the streams or rivers we crossed condescend to flow over it. All disappear immediately on coming into contact with it, and so worm their way subterraneously to the sea.

As we neared the margin of the lake, the sun was setting, and the hills in front of us were bathed in the most beautiful tints of pink and purple, surpassing even the sunset on the Tapanuis in Otago, or the first flush of the morning on Mount Egmont.

We had still three miles to walk along a raised spit of sand, about three chains wide, which forms the barrier between lake and sea, before we reached the point to which the ferry boat from the opposite side comes across; and it was quite dark when we got there and began cooeying in earnest—cooey in earnest we did, and at our loudest, for half an hour.

We quite gave up all hopes of getting over, and were prepared to walk another four miles round by the spit, as we had been informed that the entrance to the lake had silted up. However, a final and lung-splitting effort, into which we put our whole souls, brought a feeble and distant response from the other side; and the feelings of Jessie Brown at Lucknow could not have been more enraptured than ours were when we heard it, and when afterwards we saw the dim outline of our Charon and his dusky bark approaching us.

He told us that for some time he thought we were having a game with him, till persuaded of the contrary by our pertinacity, so was slow to come over. However, in the luxury of our feelings we forgave him everything.

Of course, being in the heart of a duck country, we anticipated roast duck for supper, but we were put off with mutton chops. For a similar reason, I suppose, one can never get a bloater at Yarmouth. However, we did justice to the chops and porter, and retired to very clean and comfortable beds at an early hour. Nor did we need much rocking to cause us to sleep the well-earned sleep of the weary.

We rose next morning tolerably stiff from our heavy work of the previous day, and having made a good breakfast started off to inspect a Māori pā in the neighbourhood, which we reached just as some Māori—one of them as good-looking and strapping a fellow as I have ever seen—were unloading their canoe of a creel of gigantic dimensions, literally crammed with eels of all sizes. They handled these creatures quite unconcernedly, and chucked them into a deep pit they had dug in the sand.

There must have been nearly a thousand of them, large and small, wriggling and squirming about at the bottom of this pit, presenting to an imaginative mind a scene not unlike one described by Dante in his Inferno, and illustrated by Doré. We did not stay long in this locality, as it was not a savoury one, and we had come out of Wellington as much for change of air as anything else, so with difficulty dragging Heliodorus from the contemplation of a fascinating wahine, we recommenced our onward journey.

Owing to the silting up of the lake, which has already been referred to, it had considerably overflowed its accustomed limits, and several thousand acres were under water, to the considerable annoyance of the neighbouring runholders; nor would the Māori (so we were told), who have or pretend to have certain rights in connection with it, permit the barrier to be cut through until they had finished their fishing.

There are no other sorts of fish but eels and small native trout indigenous to its waters; but when the entrance is open, large quantities of flounders and schnapper may be caught at the mouth.

Our way lay for a mile or two near the margin, over a level carpet of soft green sward, sparkling all over with glittering dewdrops; but we were soon obliged, for the avoidance of swamps and wildernesses of flax, to turn off to the right, and get upon the main road to Featherston. The road took us past a very picturesque Māori settlement, where pigs, poultry, and piccaninnies combined to create a lively scene of noise and bustle.

Seeing a pig by the roadside, in close proximity to the remains of a pack of cards, Heliodorus suggested that we should teach that pig euchre, like Capt. Burnaby; but the attendant circumstances were not favourable, so the idea was abandoned.

We trudged along some fifteen miles under a blazing sun, and occasionally had good views of the surrounding country. On our left lay the upper and lower lakes, now merged in one large sheet of water, skirted on its farther side by wooded hills, and on the right were terraces covered with tussock, indicating by this, and by the steely blue of the sky above them, their proximity to the sea.

We passed over numerous watercourses, but very little water in them; dry river beds in fact were a striking feature in the country; and as we vainly looked up and down them, seeking for traces of water enough to cool our parched lips, we thought of Burke and Wills, and wished we were camels.

At last we came in sight of Otaraia, where we intended to halt and rest, having been bidden to do so whenever we might be in the neighbourhood; and here my stupidity in not acting on the advice of the old proverb, “Look before you leap,” went far to mar the enjoyment of the whole expedition. My punishment was a sprained ankle, which of course quite upset our original intention to complete our walk round to Wellington.

So after resting awhile at Otaraia, and being hospitably entertained, we determined to push on that evening to Waihenga. Accordingly at about six o’clock we set out, having obtained the loan of a mare and foal and a large slipper. Heliodorus went first, leading the mare by the bridle, who carried myself and the large slipper, and the foal brought up the rear, having occasionally to be “chivvied” up by Heliodorus when it dropped too far behind.

The journey at this slow rate of progression was necessarily very long, but we enlivened the route by snatches of song, and by finding out jokes where even Democritus of Abdera might have pardonably failed. We reached the bridge over the Ruamahanga at about 9 p.m., and were soon comfortably housed in Schwartz’s Hotel, an inn provided by Government, very well furnished, and leased to the present occupant for twenty-one years.

Though the hotel was crowded we obtained a very comfortable bedroom. Here we found a friend who had walked over to meet us from Featherston; but having given us up had gone to bed, from which place of repose he was soon turned out.

The next day I devoted to the sofa, while Heliodorus and our friend went to knock over some rabbits—a kind of cattle which are doing a great deal of harm in the district. At one time it used to be famous for wild pigs, all the land right away up to the coast being infested with them; but extermination by contract has considerably lessened their numbers, and though frequently to be met with, they are no longer the nuisance they used to be.

The Ruamahanga and its tributaries are liable to sudden and excessive floods; and though the main channel of the numerous watercourses we had come over was never greater than one could jump across, still we could see the drift marks of the overflow in some places three or four chains wide, all this wasted land being of course nearly worthless.

Another indication of the violence and extent of the floods was given us by the fact of the fences for long distances on each side of these creeks being constructed on the swing principle, so that while the posts were firm in the ground a minimum of resistance was offered by the intermediate parts.

Next morning early we set out for Featherston, I getting a lift in a buggy and my companions doing it on foot, and thence we somewhat ignominiously proceeded to Wellington by coach and rail, feeling, perhaps, rather small at not having carried our contemplated walk into effect, but yet on the whole well satisfied with the amount of pleasure we had extracted from it.

And so comes the finis chartaeque viaeque.